Essays John Kelly at the RHA Ashford Gallery

Essay written for the catalogue of the Ashford Gallery posthumous exhibition of “A Selection of Works from his Studio” by John Kelly RHA, January 2009.

This exhibition is not a retrospective in the generally accepted sense of the term.It is, rather, a celebration of aspects of the life and work of an artist who was renowned for so many achievements in so many areas of artistic endeavour.

John Kelly was truly a man of many parts. A playwright who had his work performed in the Gate Theatre, he also enjoyed considerable success when he designed for the stage. He was known principally as a painter and a printmaker, although this sounds limiting and reductive in the light of his other significant attributes.

When we consider that he was a founding member of the Independent Artists group –the “Young Lions” of Irish art in their day – one of the prime movers behind the initiation of the Project Arts Centre in the late 60s, Director of the Graphic Studio, one of the founders of the Black Church Print Studio, a highly respected lecturer at NCAD, a member of the RHA, and in his latter years a luminary in Aosdána, we begin to get a glimpse of the scope and range of his prodigious energy and talent.

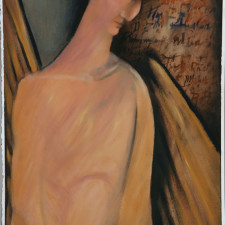

The work on display here at the Ashford Gallery spans three decades. It comprises a selection of pastels, oils and watercolours on paper and also includes a set of significant self portraits executed in pencil. It is indicative of some of the main thematic interests which he pursued in the latter part of his career. The Icarus series is represented by three pencil studies from his hugely successful exhibition in 1996. Kelly exploited the Icarus theme to enormous effect and gave it a profound conceptual span. What appears to be a desire to explore and express the visual possibilities of the winged figure in reality becomes a metaphor for the process of creativity itself. The story of Icarus is not one of hubris – it is a testimony to courage and creativity in the face of fallibility and fear.

As a younger man Kelly produced a body of work which reflected an interest in religious subject matter. This evolved over time into a spiritual exploration which resurfaced periodically in all aspects of his later work.

This is evidenced particularly in the series of pastels depicting clowns and harlequins. He was fascinated by the theatre. The theatre offered intriguing possibilities for subverting and/or altering the self. These costumed figures have no fixed or determined identities yet their humanity is unequivocally affirmed. They reflect isolation, introspection, loneliness, anonymity and vulnerability. They are consummate forms of existential expression. Stylistically they recall the mannerist figures of El Greco and to a lesser extent Goya in their distorted colours, shapes and undetermined settings. Speaking as they do, of a quiet inner turmoil and conflict they are highly expressive and dramatic but never theatrical. They display an interest in formal constraints but in the main they articulate concisely the distinction between subject and content. Like Icarus the harlequins are a figurative device to facilitate a more profound enquiry into the themes of humanity and identity.

This creative device was very much in keeping with the founding impulses underpinning the Independent Artists group. They shared a common purpose in that they espoused a type of art which was very much of the European school, naturalistic, non-academic, socially activated, urban focused, expressionistic figuration.

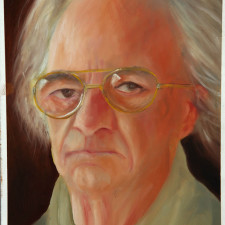

Kelly exemplifies this succinctly in his self portraits. He made forays into self portraiture on a number of occasions throughout his career – particularly as he grew older, and understood the underlying complex psychology which informs this genre only too well. Artists use the self portrait for a variety of reasons.

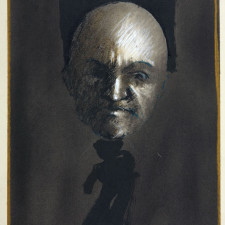

From ancient Egypt to the present day the underlying psychology of the portrait has barely altered. The self portrait is not merely concerned with self resemblance. It speaks of self projection – seeing the self as one would wish the world to see. Durer excelled in this practice. Chagall painted fantasy self portraits and located himself in an idealised location from his childhood. This was how he sought to define himself. Picasso devised the narrative self portrait which sought to essentialise the inner self to the complete exclusion of superficial resemblance. Rembrandt and Van Gogh put the focus firmly on self study and scrutiny – unromantic and real. This is the tradition with which John Kelly felt sympathetically engaged. His self realisations are measured and calm as can be seen in his self portrait in a black suit. This has a mannered Spanish expressionist flavour to it – very much of the European school.

Of particular note however in this exhibition are the pencil portraits. These were made when Kelly was in hospital. They are dated and time-logged. He had been told that he did not have very much time left to live. He made six in all. They are a testament to courage and honesty – the virtues for which he was so consistently well known during his life. He included a wilted rose in one of the studies – the meaning and significance of which is readily discernible. These portraits, containing as they do a very strong emotional charge, are the very antithesis of sentimentality. They are Heroic documents.

The last painting that John Kelly made is entitled ‘Still life with Yukio’. This was still on the easel in his studio when he died. The image is formally composed. It depicts his daughter’s deaf white cat -‘Yukio’- sitting on a table beside a bowl of carnations, – the symbol of love and marriage -and a bottle of wine. It reads as a quiet meditation on the ephemeral nature of life. The mood is tranquil without being melancholic. It is an affectionate Intimiste lyrical statement.

John Kelly was a highly accomplished practitioner of the art that conceals art . It was Duke Ellington,the great jazz pianist who once remarked that ‘an artist must say it without saying it.’

Both in life and in art this was the essential Kelly.

Gerry Walker, January 2009