Press Cuttings Introspective works make a fitting tribute to John Kelly

Currently showing at the Ashford Gallery is a fitting, thoughtfully devised tribute to the late John Kelly. Kelly, a much-liked figure who died in March 2006, is best known for his work as a painter and printmaker, though he was also closely involved in some of the most significant cultural initiatives in Ireland during his lifetime, including the establishment of the Independent Artists group, the Project Arts Centre in Dublin, the Graphic Print Studio and the Black Church Print Studio.

He was also a playwright, a teacher at NCAD and was associated with the development of the Ashford Gallery within the RHA, serving on the programme committee for several years.

The Ashford has been a resoundingly successful initiative on the part of the “new” RHA. It’s interesting that, historically, Kelly would not have been aligned with the old academic guard, and was wary about eventually joining. This isn’t because he rejected tradition: he was in almost all respects a traditional artist. But he was also open.

Sympathetic to a view of art as a process of free inquiry, he was uneasy about subscribing to what was a fairly rigid academic orthodoxy. In introducing the show, for which he was curator, Mark St John Ellis of the Ashford pays tribute to Kelly’s thoughtful contribution to programming, and his tactful way of conveying his opinions. The exhibition, St John Ellis points out, is not a retrospective. For one thing, it’s much smaller than a retrospective would have to be. For another, it’s selected from two highly personal bodies of work.

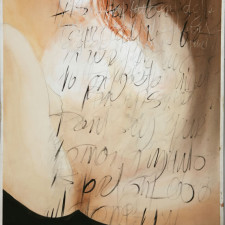

One is the material, much of it unsigned and undated, left in Kelly’s studio at the time of his death. The other is a remarkable series of self-portrait drawings made in hospital. Having suffered a heart attack late in 2003, Kelly was told, just before Christmas, that he was dying. His response was to make a series of six extremely direct, soul-searching self-portraits over three days in December. They, together with the small oval mirror he used, are there in the Ashford.

In their observational honesty, the determination they embody and their complete lack of artfulness and sentimentality, they are typical of his general approach to art.

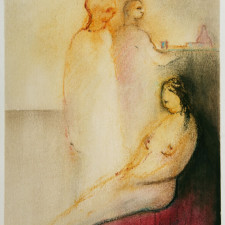

Yet as an artist he was not at all harsh. He preferred a gentle, indirect approach, creating an imaginative space in which to reflect on questions relating to life, and our place in the world.

Often these reflections took an allegorical form. The myth of Icarus was a theme that engaged him over a long period of time, and there are several good Icarus works included in the show. In his hands, Icarus is a figure emblematic of human doubt and hesitancy rather than over-reaching ambition. We live, he seems to imply, within the compass of self-imposed limitations. It is self-doubt that ultimately contains us, but at the same time he loved this area of doubt, because it is where we are truthful about ourselves, which is what an artist should be.

Introspection is the dominant mode of his work. He developed a cast of characters, often quite theatrical in character, and including a harlequin as one of several alter egos. The characters are usually dreamers, lost in their own thoughts. They are figures in space, or in a space, and the space is every bit as important as the figures. Kelly liked the infinite subtleties of spatial depth afforded by the techniques of printmaking and the use of pastel, and one can see why.

It’s as if he discovered what he wanted to represent through the process of creating endlessly recessive layers of tone rather than just setting out to make a representation of some specific subject.

Disenchantment leavened with humour is one way to summarise the view of life that comes across in much of Kelly’s work. The honesty of his engagement is central. He was not an artist with great, innate technical facility, but then many of the greatest artists are not. He was entirely true to himself and the world around him. The exhibition, in the range of work on view and its sense of incompleteness, provides a good account of the artist. So too does an accompanying publication, a beautifully designed book with several texts, including an extraordinary one by his daughter, Catríona.

John Kelly – A Tribute Exhibition. Ashford Gallery, Royal Hibernian Academy, Gallagher Gallery Until Jan 29 01-6612558.

This article appears in the print edition of the Irish Times

Aidan Dunne, Irish Times, 14.01.2009